Dharamshala: - A study led by researchers from the University of Utah in Salt Lake City, Utah, United States has discovered the genetic reason that Tibetans can live without medical complications on the Himalayan Plateau of Tibet, which has an average elevation of 14,800 feet.

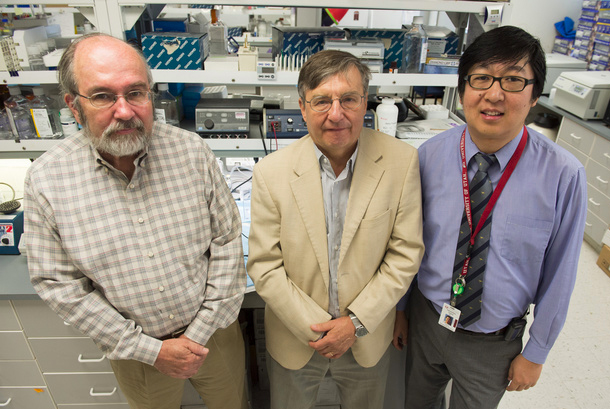

According to media reports, 'the results of the study, led by senior author Josef Prchal, an internist and hematologist at the Uiniversity were published online on Sunday in the journal Nature Genetics. By taking blood samples from 26 Tibetans living in Utah and Virginia — as well as dozens more from Tibetans and other Asians living in China and India — they found the gene EGLN1 changed by a single DNA base pair.

Lowlanders who lack the genetic mutation suffer in thin air because their blood becomes thick with oxygen-carrying red blood cells in an attempt to feed oxygen-starved tissues, Kristen Moulton has reported in 'The Salt Lake Tribune.

That can lead to long-term complications such as acute mountain sickness or heart failure, but Tibetans' bodies do not react to high altitude by producing extra red blood vessels, Prchal said.

The mutation apparently began 8,000 years ago and "spread like fire" through the population, he said. Those who had it thrived and, by natural selection, their offspring did too. Today, 88 percent of Tibetans have the genetic variation, but it is virtually absent in closely related lowland Asians, the study found.

DNA from Chinese, Japanese, Koreans, Mongolians and Filipinos were compared against the Tibetan DNA. "The significance is ... that we understand more about evolution," said Tsewang Tashi, a research associate at the university's Huntsman Cancer Institute and one of the study's authors.

Tashi, who was born in India to Tibetan parents, came to the University in 2012 and was a great help during visits to Asia, Prchal said, adding he began the research in 2007. There is much more to be learnt, and it was complicated by cultural and political difficulties.

Tashi knew the culture and language and could help Tibetans understand the research, Prchal said. Tashi also recruited Tibetans living in Utah and Virginia to donate their blood for DNA testing.

"We are all saying we are not Chinese, and this proves it," said Pema Chagzoetsang, a program specialist for the state homeless program, who also recruited other Tibetans living in Salt Lake City. Chagzoetsang, who was just 10 months old when her parents fled Tibet over the Himalayas in 1959 to escape the communist regime in China, was one of those donating her blood for the study.

Prchal is thinking more along medical lines. "This mutation is extremely important because it regulates many functions in the human body," he said.

Prchal was also able to meet with His Holiness the Dalai Lama in Prague, Czech Republic, and the Tibetan people's spiritual leader wrote a letter endorsing the research. Prchal and His Holiness the Dalai Lama had a mutual friend — now-deceased Czech Republic President Vaclav Havel — and that helped, said Prchal, who fled communist Czechoslovakia in 1968.

A partnership between Qinghai province in the north of China and the university, formalized when former Utah Gov. Jon Huntsman was ambassador to China, laid some groundwork. Prchal was able to do research at the Research Center for High-Altitude Medicine of Qinghai University and initial results were published in 2010.

It might have implications for cancer research, and also for diabetes or high blood pressure at low elevations. One of the study's authors, University endocrinologist Donald McClain, for instance, continues to research a connection between obesity and diabetes.

![Tibet has a rich history as a sovereign nation until the 1950s when it was invaded by China. [Photo: File]](/images/stories/Pics-2024/March/Tibet-Nation-1940s.jpg#joomlaImage://local-images/stories/Pics-2024/March/Tibet-Nation-1940s.jpg?width=1489&height=878)